One of the most appealing and inspiring subjects in Inayat Khan’s lectures is the Music of Life. For this reason we named our cultural events The Music of Life, a project that Saki and I started in 2014 to bring together people of diverse background through poetry, storytelling and music. In this article I would like to explore a lecture of Hazrat Inayat Khan on music and mysticism, where he elaborates artfully on ideas also expressed in Rumi’s Masnawi. In both their writings music is used as a metaphor for the depths of life.

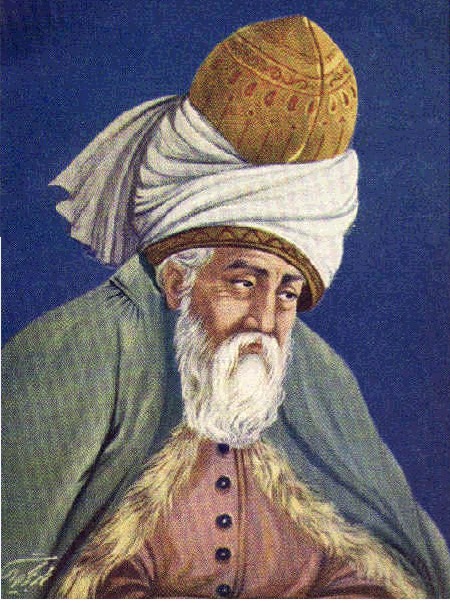

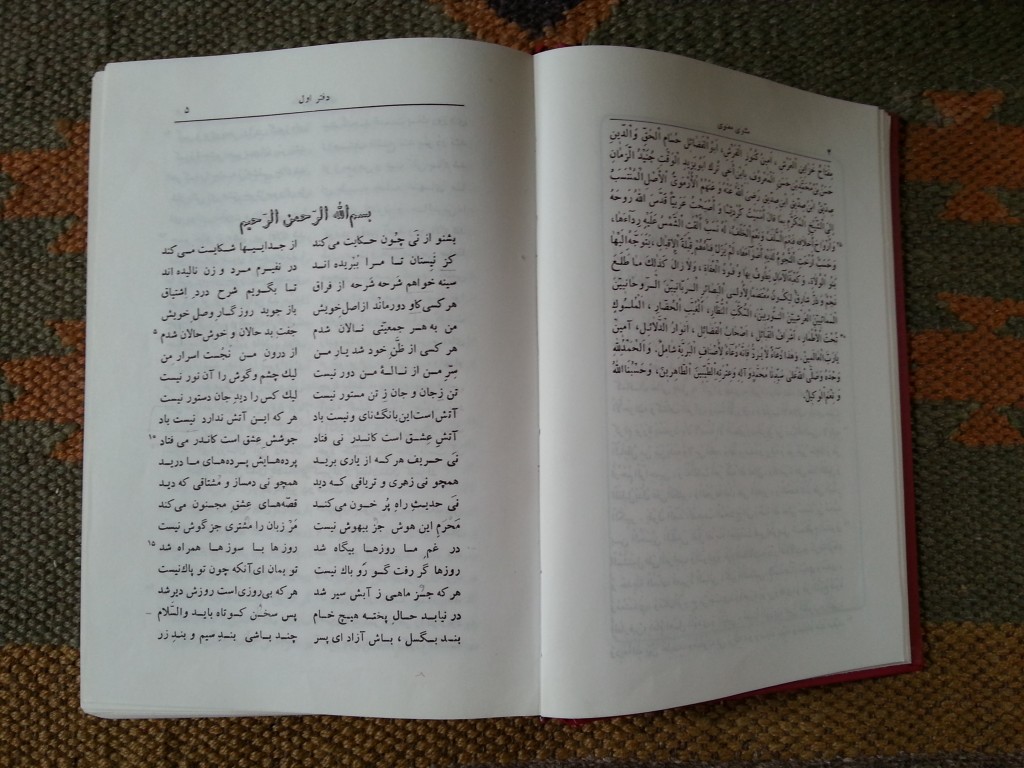

Rumi says:

We are like a harp,

you strike us with the plectrum.

The lamentation is not from us;

it is you who is lamenting.

We are as the flute,

and the music in us is from You;

we are as the mountain,

and the echo in us is from You.

[Rumi, M. I, 599]

These lines are from a story about the Jewish king and the Christians. It is a treatise on our human interactions, with all its cunning and manipulation, but also serving a higher purpose. In other words: Even within “free will” our actions are part of a cosmic story unfolding.

Hazrat Inayat Khan starts off: “The music of life shows its melody and harmony in our daily experiences. Every spoken word is either a true or a false note, according to the scale of our ideal. The tone of one personality is hard like a horn, while the tone of another is soft like the high notes of a flute. The gradual progress of all creation from a lower to a higher evolution, its change from one aspect to another, is shown as in music where a melody is transposed from one key into another. The friendship and enmity among men, their likes and dislikes, are as chords and discords. The harmony of human nature, and the human tendency to attraction and repulsion, are like the effect of the consonant and dissonant intervals in music.”

The music of David

affected rock and mountain,

but the ears of those stony-hearted ones

heard it not.

[Rumi M. III, 2833]

These lines are part of a story about the significance of the prophets; the destructive effect of people who deny the truth; and the abuse of parables. In book two in a story about the envious servants of a king we can find a similar line: “The melodies of David were so dear to the faithful, but to the unbelievers they were no more than the noise of wood. A reference to Qur’an (Yusuf), 12:1-2: “These are messages of a revelation clear in itself and clearly showing the truth. Behold, We have bestowed it from on high as a discourse for people who listen and understand.” This means that music in the philosophy of the sufis has revelatory qualities for those who want to hear.

Hazrat Inayat Khan continues: “In tenderness of heart the tone turns into a half-tone, and with the breaking of the heart the tone breaks into microtones. The more tender the heart becomes, the fuller the tone becomes; the harder the heart grows, the more dead it sounds.”

When the harpist who plays

the four-and-twenty musical modes

finds no ear to listen,

his harp becomes a burden.

[Rumi, M. VI, 1657]

These lines follow a heading which goes like this: “The Prophet said: Verily God teaches wisdom by the tongues of the preachers according to the measure of the aspirations of those who hear them.” In other words: If nobody listens in the audience, there is no inspiration, and nothing comes to mind. If the opposite happens, a whole world from the unseen opens up with every note, scale or word. These experiences of whirling and pulsing exaltation stay with us our entire life and beyond.

Hazrat Inayat Khan adds to this: “Each note, each scale, and each strain expires at the appointed time, and at the end of the soul’s experience here the finale comes. But the impression remains, as a concert in a dream, before the radiant vision of the consciousness.”

The solitary mountain

amidst that cloud of darkness

opens the music of the harp

and the tones of treble and bass.

[Rumi, M VI, 2285]

These lines from Rumi’s Masnawi are from the story about the Fakir and the Buried Treasure. It’s about a dervish who, after a tiresome search for a Hidden Treasure, suddenly realizes that God is our guardian and that we are guided through in all life’s endeavours. A reference to the Divine Saying: “I was a Hidden Treasure and loved to be Known.” A voice of inspiration speaks to him: “It was said to put an arrow in the bow, but was anything said about drawing the bow? The voice didn’t tell you to draw the bow very hard, it said to put the arrow in the bow, not to shoot it with all your might. Out of vanity you picked up the bow and wanted to show off your archery skills. Stop this display, keep the arrow in the bow and don’t try to shoot as far as possible with force and violence. When the arrow falls to the ground, go to the cut spot and search. Give up stupid strength and seek the gold with humility and supplication.” In other words don’t try too hard, the treasure you are looking for is right under your feet!

Hazrat Inayat Khan goes on to say: “With the music of the absolute the bass, the undertone, is going on continuously, but on the surface and under the various keys of all the instruments of nature’s music the undertone is hidden and subdued. Every being with life comes to the surface and again returns whence it came, as each note has its return to the ocean of sound. The undertone of this existence is the loudest and the softest, the highest and the lowest. It overwhelms all instruments of soft or loud, high or low tone, until all gradually merge in it. This undertone always is, and always will be.

The mystery of sound is mysticism; the harmony of life is religion. The knowledge of vibration is metaphysics, and the analysis of atoms science; their harmonious grouping is art. The rhythm of form is poetry, and the rhythm of sound is music. This shows that music is the art of arts, and the science of all sciences, and it contains the fountain of all knowledge within itself.”

From within them

musicians strike the tambourine;

at their ecstasy the seas

burst into foam.

You see it not,

but for their ears

the leaves too on the boughs

are clapping hands.

[Rumi, M. III, 99]

These lines are from Rumi’s story about the men who ate a young elephant. The hungry dervishes didn’t listen to the advice of their mystic teacher — who had insight into the natural law of cause and effect — not to eat the flesh of a young elephant. The mother elephant at her return was able to sniff out the men who ate her elephant son and killed them all, except the teacher who warned the dervishes for this kind of greed. These verses depict the cosmic consciousness of the mystic who is one with the universal spirit objectified in the world of nature, so that he enters into the life of all things. To him seas and woods are vocal with divine harmonies — echoes and reflections of the music in his heart.

Hazrat Inayat Khan says in his lecture: “Music is called a divine or celestial art, not only because it is in itself a universal religion, but because of its fineness in comparison with all other arts and sciences. Every sacred scripture, holy picture or spoken word produces the impression of its identity upon the mirror of the soul, but music stands before the soul without producing any impression of this objective world in either name or form, thus preparing the soul to realize the infinite.”

The Prophet has said

that the true believer is like a lute,

which makes music only

when it’s empty.

As soon as it’s filled,

the minstrel lays it down—

don’t become full,

for sweet is the touch of His hand.

Become empty and stay happily

between His two fingers

for “where” is intoxicated

with the wine of “nowhere”.

[Rumi, M. VI, 4213-15]

These are two verse lines from a story about a treasure seeker from Baghdad. He had dreamed — after squandering his inherited money and estates, and was left destitute and miserable — that his hope to find a fortune would be fulfilled in Cairo, but arriving in Cairo he met someone who said he had a dream that there was a treasure in the house of the first man in Baghdad. Rumi inserts a line addressed to the reader: “O such and such, you don’t know the value of your soul because God bountifully gave it to you for nothing.” Once he realizes that he is left empty handed, desolate like an owl in the desert, he cries: “O Lord, You gave me provision: the provision is gone: either give me some provision or send death.” When he became empty, he began to call onto God. He started the tune of “O Lord!” and “O Lord, protect me!”

Hazrat Inayat Khan continues: “Recognizing this the Sufi names music ghiza-i-ruh (غزای روح), the food of the soul, and uses it as a source of spiritual perfection; for music fans the fire of the heart, and the flame arising from it illumines the soul. The Sufi derives much more benefit from music in his meditations than from anything else. His devotional and meditative attitude makes him responsive to music, which helps him in his spiritual unfoldment. The consciousness, by the help of music, first frees itself from the body and then from the mind. This once accomplished, only one step more is needed to attain spiritual perfection.

Sufis in all ages have taken a keen interest in music in whatever land they may have dwelt. Rumi especially adopted this art by reason of his great devotion. He listened to the verses of the mystics on love and truth sung by the qawwals, the musicians, to the accompaniment of the flute.

The Sufi visualizes the object of his devotion in his mind, which is reflected upon the mirror of his soul. The heart, the factor of feeling, is possessed by everyone, although with everyone it is not a living heart. This heart is made alive by the Sufi who gives an outlet to his intense feelings in tears and in sighs. By so doing the clouds of jelal, the power which gathers with his psychic development, fall in tears as drops of rain, and the sky of his heart is clear, allowing the soul to shine. This condition is regarded by the Sufi as the sacred ecstasy. The masses in general, owing to their narrow orthodox view, have cast out Sufis, and opposed them for their freedom of thought, misinterpreting the Prophet’s teaching which prohibited the abuse of music, not music in the real sense of the word. For this reason a language of music was made by the Sufis, so that only the initiated could understand the meaning of the songs. Many in the East hear and enjoy these songs not understanding what they really mean.”

Samá‘ is the food of lovers of God,

for within it is the taste of tranquility of mind.

From hearing the sounds of the flute

the mental images become stronger

until they take shape in the imagination.

The fire of love is fueled by melodies.

[Rumi, M IV, 742]

The verses above are part of a Rumi story about Ibrahim Adham: a prince who left his kingdom, to give all his possessions away, and to disappear. After hearing the sound of the rebeck on the roof of his palace he comes to the realization that sitting on the throne is not the right way for him to seek God.

The Mevlevi sama’, undoubtedly originating from an upwelling of ecstasy, has been explained as a representation of the planets stirred by love and longing, to circle around the sun, a motionless Mover.

Hazrat Inayat Khan ends this section with: “Since the time of Rumi music has become a part of the devotions in the Mevlevi Order of the Sufis. A branch of this order came to India in ancient times, and was known as the Chishtia school of Sufis. It was brought to great glory by Khwaja Moin-ud-Din Chishti, one of the greatest mystics ever known to the world. It would not be an exaggeration to say that he actually lived on music. Even at the present time, although his body has been in the tomb at Ajmer for many centuries, yet at his shrine there is always music given by the best singers and musicians in the land. This shows the glory of a poverty stricken sage compared with the poverty of a glorious king: the one during his life had all things, which ceased at his death, while with the sage the glory is ever increasing. At the present time music is prevalent in the school of the Chishtis, who hold meditative musical assemblies called sama or qawwali. During these they meditate on the ideal of their devotion, which is in accordance with their grade of evolution, and they increase the fire of their devotion while listening to the music.”

Sources:

Reynold A. Nicholson, The Mathnawi of Jalalu’din Rumi, Volume 1-8, Cambridge, 1933.

Hazrat Inayat Khan, The Sufi Message of Hazrat Inayat Khan, Volume 2, The Mysticism of Sound (p. 57-60), Richmond (USA), 2017.

Safavi and Weightman, Rumi’s Mystical Design, (Reading the Mathnawi, Book one) Albany, 2009.

Kenan Rifai, Listen (Commentary on the spiritual couplets of Mevlana Rumi), Louisville (USA), 2010.